Controlling the Worm Cycle

Worm Resistance |

|

If worms survive a drenching they get to breed and pass on that genetic advantage. The numbers of those with this advantage grow while those with no special resistance diminish. Eventually, the drenches we use become less effective because more resistant worms are surviving. We know that we can slow this process by using different drench families, which means that we can kill some of the resistant worms with a different chemical, but it is little more than a delaying tactic.

|

What types of worms are there and what problems do they cause? |

How are worm infestations diagnosed?Typical signs and symptoms (including ill-thrift, weight loss, colic, diarrhoea) and poor quality management (overcrowding, inadequate and contaminated grazing, and inadequate use of effective wormers) often suggest that intestinal parasitic problems are most likely.

Laboratory investigations are the definitive method of diagnosis. Two types of tests are performed: 1. Dropping samples are analysed to count the number of worm eggs per gram of faeces. This gives an indication of the types and number of adult worms present in the intestine that are producing eggs. False negative results can occur when the adult worms are not producing enough eggs to be detected and this can sometimes occur when the horse is very unwell. Dropping samples are most useful when collected from all or presentative batches of horses on a routine and regular basis to monitor the success of a worm control programme. Generally worm egg counts below 50 eggs per gram (50 epg) are not concerning. 2. Although blood samples are often suggested to help diagnose parasitism, the results of most tests are nonspecific and hard to interpret. There is, however, a specific blood test which has been developed to demonstrate tapeworm infestations. How can I make sure my horses do not suffer from parasitic worms?Whether you own one horse or a whole stud farm, you should develop a worm control program. This will be based upon many factors including your geographical location, the types and ages of horses that you have, your stocking density and the frequency with which horses come and go at your premises. Effective parasite control depends upon both management of grazing to minimise worm eggs and larval contamination and the use of wormers to remove parasites from the horses’ intestines. One cannot be adequately effective without the other.

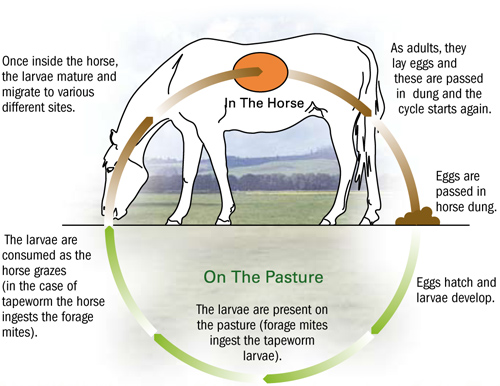

How can I best manage my available grazing?Horses re-infest themselves by eating parasitic eggs or larvae by grazing on contaminated pasture. Therefore:-

1. All horses grazing on the pasture should be well wormed to reduce their output of parasitic eggs and larvae. 2. New arrivals should be treated with an effective wormer on arrival and should be separated and manure removed for twp to three days before being turned out onto clean pasture. 3. The pasture should not be overcrowded so horses can avoid eating contaminated grass. 4. Droppings should be frequently and regularly picked up if horses are living in crowded pastures (twice weekly should be sufficient) and removed from the pasture to minimise contamination. If you have sufficient acreage, mechanical ‘dropping pickers’ (vacuum-type devices powered by small tractors), are particularly effective. This approach is extremely effective at reducing parasitism (perhaps more so than worming!) and should always be encouraged. 5. If possible, paddocks should be regularly grazed with other species such as cattle or sheep, in rotation and then rested. These animals are not affected by equine parasites, their parasites do not affect horses, they graze more evenly than horses and their droppings stimulate good grass growth. Three months of horses not in the paddock will develop a 'clean' paddock. |